Dateline, 6/19/2020:

If you’ve been following along in the Quarantine series (linked at the bottom of the page), you know that I came upon some reduced pricing on specialty meats as a result of the pandemic driven restaurant industry collapse. Veal breast is one of those things you really never see on retail OR wholesale inventory lists. The term itself refers to the anatomical equivalent of a beef brisket with the bones still attached. It looks vaguely similar to pork spare ribs, again, as a result of a general anatomical correspondence.

In traditional cuisine, veal breast was usually stuffed, roasted and carved–at least until a sort of “cuteness backlash” and the cost of production caused veal to fall into disfavor. Veal was popular in Europe but it never really did catch on in the states. Osso Buco here and there, Scallopini or Parmigiana now and again, but not much in the retail market. Veal breast is sort of what’s “left over” after the chops and legs and shanks are portioned out. It’s at least half bone, and to be honest, that’s why I bought it. It was cheap enough to take advantage of the opportunity to make a “real” demi-glace. I figured I would just burn through the meat one way or the other. As it turned out, at about $3/lb, it ended up being a good value both ways.

Frozen on delivery, you can at least see that it really has that “milk fed” color.

If you can imagine, those bones are a profile of the sternum, just like on spare ribs, as I mentioned. The lower left has the same appearance as the point end of the beef brisket, right?

Flipped over, that “point” end.

And here’s the other end, again, the strong resemblance to the pork spare ribs. That flap you see is the all so mysterious “skirt steak.”

Skirt steaks are a mess, especially when they’re this small. I set it aside though and processed it with everything else, more on that in a minute.

The flat end, the tail end, again the resemblance to pork spare ribs.

Apologies to professional butchers, I removed the bones from the meat the best I could. But it’s not just point and flat. In the course of removing all that meat, I removed what is colloquially referred to as the “short ribs,” or what would be on a steer. Not much meat to it, but we will see a bit of it later.

Giving me this, about 6 lb. of meat, and 6 lb. of bone all in all.

Minimal trimming, I cut the muscle group into six squares. The back row is thinner, mostly “flat.” The front row is where the flat intersects with the point, so they are thicker. I reserved the thick ones for another post, we will be dealing with the back row and the skirt steak section.

Preheat the sous vide bath to 135 F/57 C.

Vacuum seal the veal breast portions in a heat rated bag and process at

135 F/57 C for 24 hours.

I thought it would go faster. It didn’t, but it doesn’t matter. It goes until it’s tender, there is no other protocol. Once the processing is done, cold shock the packages in iced water until they achieve 70 F/21 C and refrigerate at 40 F/4 C. Sealed packages will keep in this state at least two weeks.

While we wait

Preheat the oven to 350 F/176 C.

Roast the bones until they achieve the fully darkened color–about 2 hours.

When they’re done, put them in a pot with 2 gallons of tap water and bring to a gentle boil. I used a silicone mat so all the drippings peel right off. Silicone mats are a great investment–not expensive, and they save a lot of scrubbing.

If you have the shelf space, roast 3 carrots and 6 stalks celery, lightly oiled, at the same time–the oil helps them brown and gets removed later anyway. After an hour, add 2 onions coarsely cut and roast another hour until….

You get this. Add this to the stock pot.

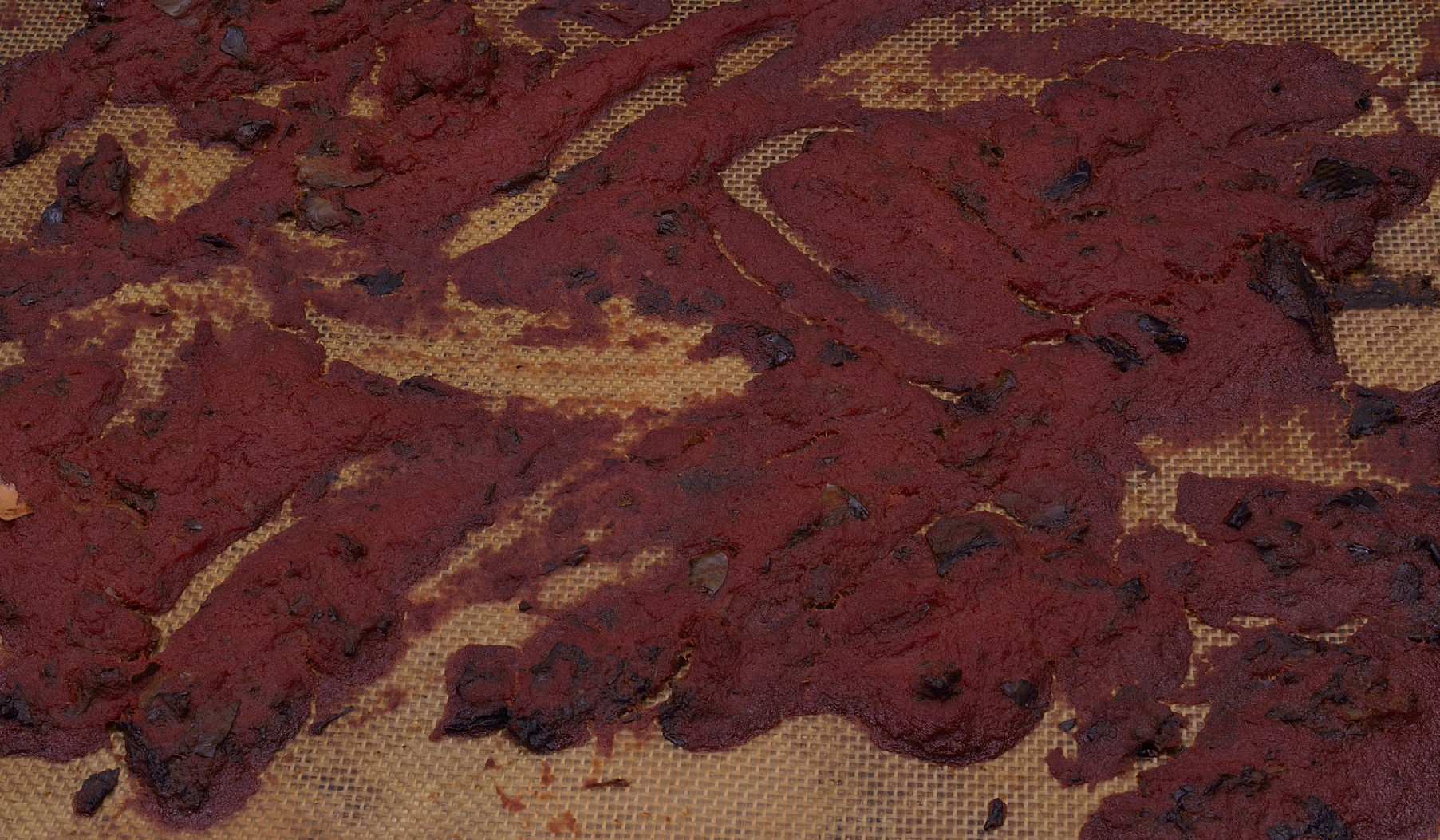

Pour a 15 oz can of plain tomato sauce on a silicone mat (preferably)…

and roast for an hour or so until you get this–stir once…

If you use the mat, the caramelized tomato paste comes right off and goes into the stock pot. If you don’t use the mat you have to make do, dissolve in water, etc.

Simmer the stock for at least four hours, up to 12, but do not allow to reduce. When the meat falls off the bone, empty the stock pot through a colander into a large container to get the large pieces out. Now comes the clever part.

Let’s make something perfectly clear

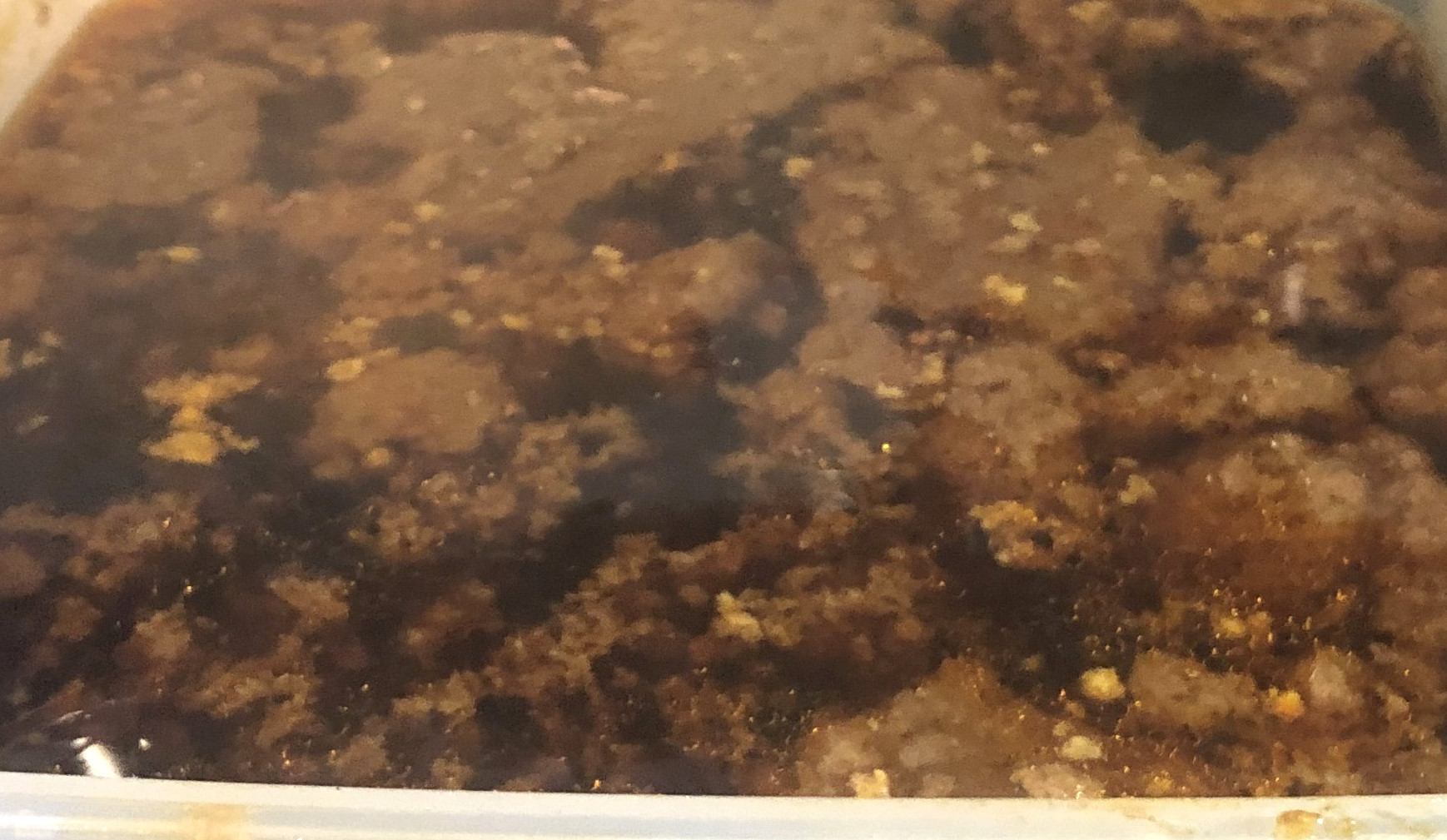

Add four Tablespoons of powdered egg white and 1 cup of COLD water to the stockpot (or four egg whites). Mix well with a whip or stick blender. You don’t need meringue, but you want it a little foamy. Add the hot (not boiling) stock to the stock pot with the egg whites in it. The whites have a tendency to sink at first, so stir gently with a wooden spoon or spatula while you return the stock to a gentle simmer. After a few minutes you will get something that looks like this:

The egg whites coagulate as they denature. While doing so, they attract all the other denatured myoglobin and albumins that are floating around in the stock.

Put a colander in a large clean container, line it with wet paper towels. The towels must be wet to prevent the stock from clinging to them.

Pour the stock through the paper towels.

This is what you get–lots of it. At this stage, it is brown stock. As it reduces, it eventually becomes demi-glace and then glace de viande, or at least an approximation of it. There is a lot of gelatin in it, and if you reduce it far enough, it usually does not need any salt. This is an ingredient in pan sauces that most cooks seem to have forgotten accidentally on purpose.

Above: that’s about 2 quarts of brown stock reduced to half a cup.

Remember that scrappy looking skirt steak?

I shocked that raggy little piece, cut it into approximate scallopini shapes, seasoned it and dredged in flour.

I then sauteed it more or less according to the thousands of Veal Scallopini recipes that are all over the net, with the tomatoes and without the mushrooms. A little cold butter dissolved in the sauce at the last moment creates the sheen–everything is an emulsion.

It was an impromptu lunch. You can see how much of a difference a little brown stock makes in there. Parsley.

Moving on:

I used the same basic prep model for the thinner pieces:

Remove from package and pat dry. Reserve the juices and either add them to the simmering veal stock or process according to the method outlined HERE.

Dust with powdered egg white or powdered buttermilk. We came across the buttermilk idea to accommodate people who are allergic to eggs, it works pretty much the same. I don’t like the mayonnaise method because it melts and runs off, so don’t ask.

Spritz with just enough water to dissolve the powder.

Sprinkle with seasonings. Turn it over and repeat the process, go easy on the seasonings.

Dredge lightly with flour on both sides, shake off the excess. Heat a saute pan to 275 F/135 C. Add enough oil to coat the bottom of the pan.

Fry until crisp.

That’s going to give you this.

The cross section will look like this. That bottom layer wouldn’t be there on a beef brisket because it would be left attached to the bone to create “short ribs.” I know, very confusing.

While we’re on the subject

I’m not going to go into a myth-dispelling treatise on pan sauces right here, even though I have one at the ready. There is a widespread belief that the “drippings” left in the pan after the sauteing process dissolved in some wine is somehow the basis of a successful “pan sauce.” That is just too much to ask of those two meager ingredients. There is also a common misconception that sauteed proteins benefit from being simmered in the pan sauce to complete some form of mysterious and romantic infusion/tenderization process that does not exist in reality. I will leave it at that for now.

All these recipes/procedures/presentations start with the veal being prepared as shown, removed from the pan and then set aside. With very few exceptions, the practice of leaving the protein in the pan while making the sauce is a bad habit shortcut that cooks and chefs started doing to save space and effort. You can finish the sauce in the pan if you want to, but even that is a matter of convenience and there is nothing magic about the pan. The sauce can be made ahead. The drippings are nothing more than myoglobin and albumins that were released from the meat, just more dots in your sauce. Adding a couple shots of red wine will give you a purple sauce unless you reduce the wine to almost nothing, which could and should have been done ahead of time. Wine and drippings are not the basis of a pan sauce. STOCK–and butter, are the foundation of a good pan sauce. There, I said it. Butter.

No flames, no glory

For the veal scallopini version pictured above, I sauteed the skirt steak, removed it from the pan, added the garlic and tomatoes, some brown stock and then finished with the cold butter to create the emulsion. Once the sauce is done, you add the veal to the pan and toss with the sauce to make it LOOK like that, but you NEVER boil it again after that. Vegetables and starches are heated separately and may have their own sauce or butter. Incorporate reduced wine if you must, but a sauce need only be composed of stock, whatever components are actually IN the sauce like garlic, mushrooms, herbs, etc, and butter to get the right appearance and thickness.

Two emulsions, from two different stocks.

Heavily reduced blonde stock (un-roasted bones and vegetables) with a little butter worked into it

and the heavily reduced veal stock that we outlined here with a little butter worked into it.

No blonde butter sauce, Tamarind dots instead…

Great moisture retention, thanks to sous vide.

The closer you get, the better it looks.

Don’t call it Florentine, all those names are pretty dated. I don’t cook spinach. I toss it with salt and let it rest for an hour, which causes it to wilt and lose water. I learned that from a Greek lady. Then I wrap it in towels and vacuum it in a sv bag. I made that part up. This can be kept refrigerated for several days without losing the bright color. When I need it, I just heat some up in the sauce. Great in lasagna, quiche, all those things that always leak a bunch of blackish green spinach juice.

The cream is an emulsion, not a reduction.

1 oz of whipping cream brought to a boil with 2 oz of butter and a pinch of salt.

Point to flat

It takes very little imagination to see the similarity of these slices to the point/flat end of the beef brisket, right down to the layer of fat separating the two muscles.

The color really is more poultry-ish.

Dusted with powdered egg white.

Misted with water to create a sticky surface.

Kosher salt, white pepper, dried parsley.

Sous-jus in the pan to create the buttery emulsion, some fresh spinach.

Classic-ish

Norm

To see Part 1, Rack of Australian Lamb, click HERE

To see Part 2, Chicken Breasts, click HERE

To see Part 3A, Boneless Baby Back Ribs, click HERE

To see Part 3B, More Boneless Baby Back Ribs, click HERE

To see Part 4, Vegetables and Starches, click HERE

To see Part 5, Meaty Prime Rib Bones, click HERE

To see Part 6, Maui Nui Tenderloin, click HERE

To see Part 7, Oregon Lamb Shoulder Flap, click HERE

To see Part 8, Center Cut Pork Loin Roast, click HERE

To see Part 9, Bison Chuck Eye, click HERE

To see Part 9B, Bison Chuck Eye, Chicken Fried Bison, click HERE

To see Part 10, Sous Vide Braising of Red Meats, click HERE

To see Part 11, Beef Rib Eye, click HERE

To see Part 12, Shocking Options/Beef Hanger Steak, click HERE

To see Part 13a, Chicken Wings Crispy Style, click HERE

To see Part 13b, Smoked Chicken Wings, click HERE