Dateline, 5/14/2020: Bison in the Age of Gimme Shelter

“Where the bison roam” just doesn’t have the same ring to it…

Among many other things, the COVID19 pandemic has caused interruptions in the supply chain for wholesalers. I don’t usually have bison (meat) around, but the quarantine furled the sails of all the local chi chi restaurants. Fortunately or wisely, our friends at NickyUSA had enough inventory to keep them going during the slowdown. As a result, they have been offering discounts on elk, venison, bison and other things. Kangaroo, partridge, gator, snake, you name it, they’ve got it.

Let’s get this straight. Bison and buffalo are both members of the same taxonomical family, Bovidae, but they are not members of the same species or even genus. Common to Asia and Africa, huge-horned wild Cape Buffalo kick dust and face off with lions on the nature channel. Domesticated Water Buffalo either slog through rice paddies in those Thai travel mags or get slaughtered in “Apocalypse Now.” That scene really sticks in my head. The horror.

That leaves bison. Those are the one-ton shaggy creatures hunted to near extinction in the 1800’s. With a little help from animal rights activists, they’ve made enough of a comeback to be seen terrorizing unsuspecting tourists in Yellowstone on the news or YouTube. Six feet tall, stocky legs, short horns aimed backwards and a woolly winter coat that they shed. Both buffalo and bison are native to parts of Europe, but buffalo are not native to the Americas, only bison.

Pretzel Anatomy–eyes, hearts, and blades

“Chuck eye” is actually a formalized name for what butchers call the “clod heart.” The clod is a muscle group located in the upper part of the bison (or beef) shoulder/chuck. It includes the uniquely tender and more recently “discovered” flat iron and teres major (petite filet) cuts, which shrewd butchers routinely remove to sell separately at premium prices. Doing so creates the “clod heart.” To avoid sticking a label on the package that says “clod (heart),” it becomes referred to aspirationally as the “chuck eye.” The muscle group is described as “flavorful,” which means it is even tougher than brisket. This bison clod heart was about 11 lb/5 Kg.

Taken apart by basically following seams, we get some large pieces of various shapes. The main difference from beef is not toughness/tenderness. They are pretty much the same. But you can see the lack of marble in the buffalo. None of those streaks of fat that we are accustomed to.

Flap meat and so forth. The scrappy stuff on the right would actually be okay for bison burgers, but I needed it to make THIS. Everything (except the trim) got vacuum sealed.

Blather

People familiar with my work know that I advocate cold shocking after sv processing for almost everything. There are notable exceptions. I don’t usually shock premium steaks, for example–filets/tenderloins, rib eyes, New Yorks, etc.–chilling and then retherming CAN cause a rare steak to lose some red color. I don’t usually pasteurize premium steaks either–it’s not necessary if I know I’m going to eat them within four hours as required by food safety guidelines.

You shouldn’t shock anything cold for later use unless you are sure it’s pasteurized, as per Baldwin’s guidelines HERE. We’re going to demo the finishing process both ways–from hot out of the bath, and from cold out of the fridge.

We hybridized a “medium rare” temperature, 130 F/54 C, with a very long, collagen converting interval of 60 hours–these steaks/roasts achieve pasteurization long before the time elapses. Most of the packages were then shocked cold in iced tap water until they achieved 70 F/21 C. Those pasteurized packages were staged into the refrigerator at 40 F/4 C. You don’t HAVE to shock the packages for the food to be good, tender, or safe. I do it as a matter of convenience. Right? And we’re going to demo at least one from hot to compare. We’ll see how that all works out.

Basic Ingredients:

Bison clod, “as needed.”

Egg whites, as needed, mixed with an equal volume of cold water. A little bit of egg white makes the seasonings cling to the protein’s surface. It doesn’t take much. I buy egg whites in the carton–they are also available dried. We used dried in this demo, but the basic procedure is the same.

Seasonings, as needed.

Vegetable oil, a few drops. I use the spray stuff.

Melted butter, as needed.

Chopped parsley, as needed.

I want one right away

Gone are the days when I would watch the clock waiting for some carefully calculated interval to expire. Not only have I come to realize that there is no “moment” before which or after which, I have plenty of other things to keep me occupied. Between writing, editing, taking pics, the dog and administering the group, I put stuff in and take stuff out of the bath in between all my other diversions.

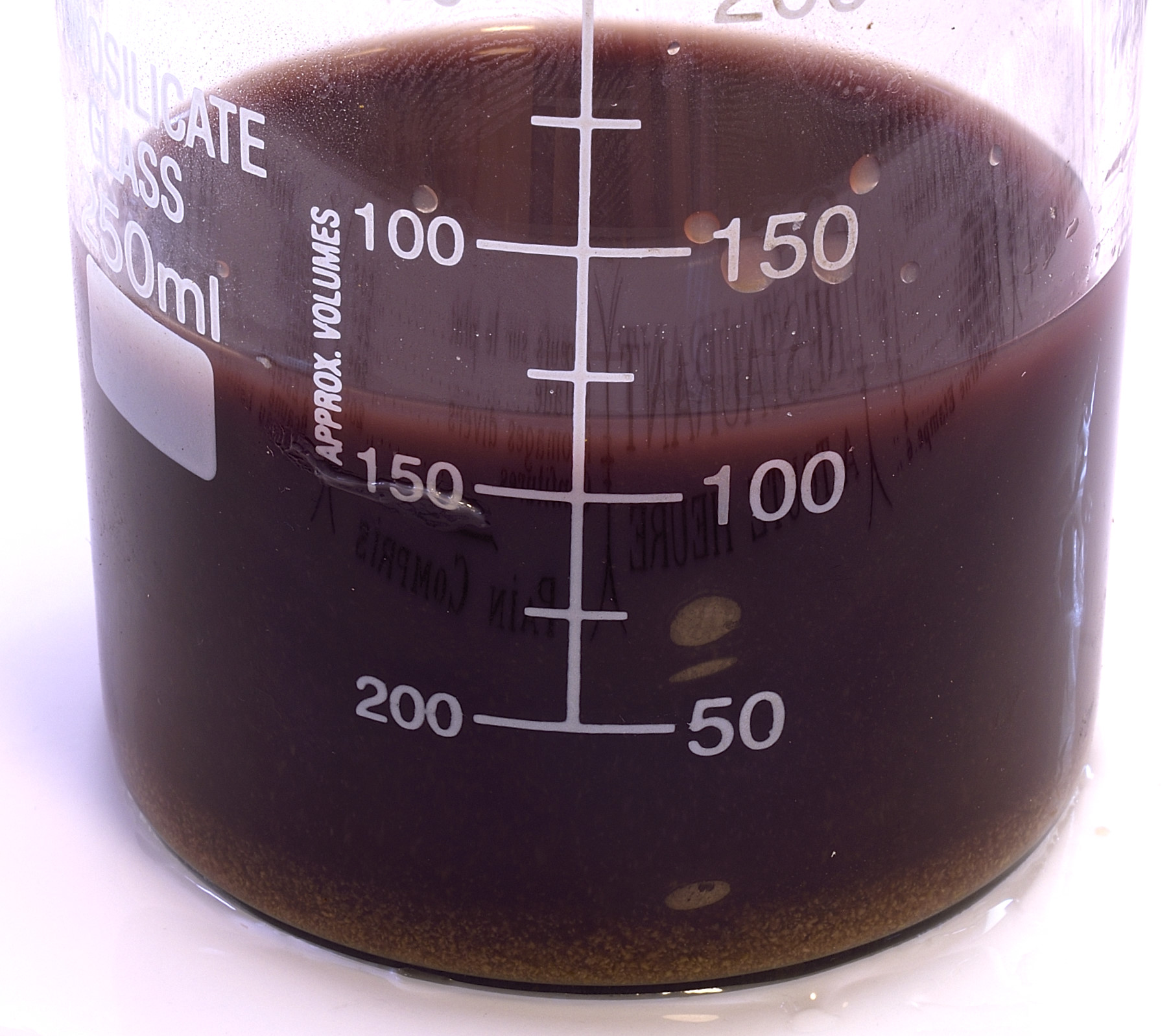

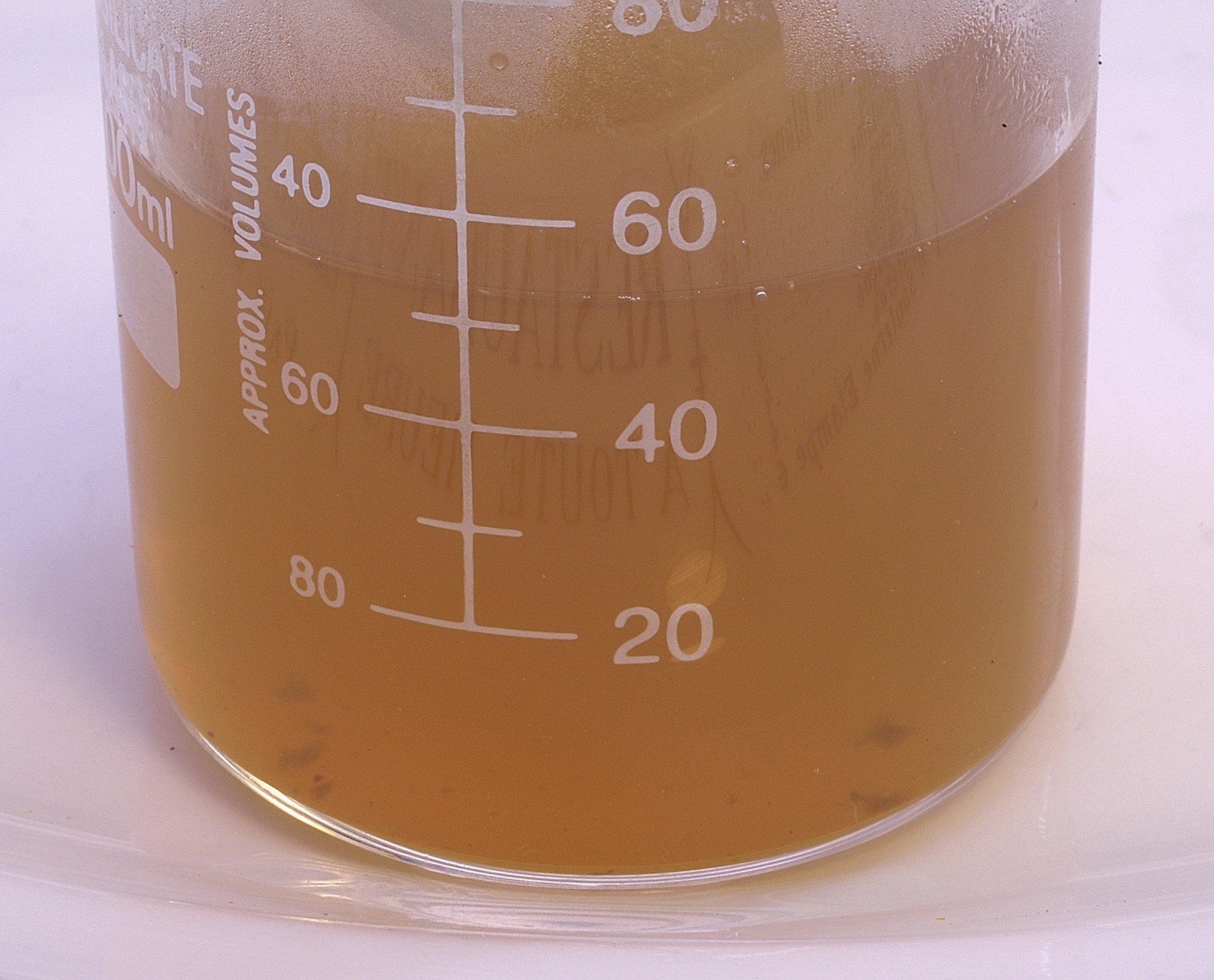

Coming out, beef and other red meats can look pretty drab. The juices can look almost purple. The denaturing of the myoglobin combined with its exposure to trace amounts of oxygen create an iron laden, greenish, mock-turtle soup sort of color. Alarming at first, people suspicious of sous vide point at this and laugh. This is normal.

The unfiltered purge has myoglobin and albumins dissolved in it that are not fully denatured at this temperature. You can see that there is no fat floating on the top though. Sous vide does not render much fat, not even at higher temps.

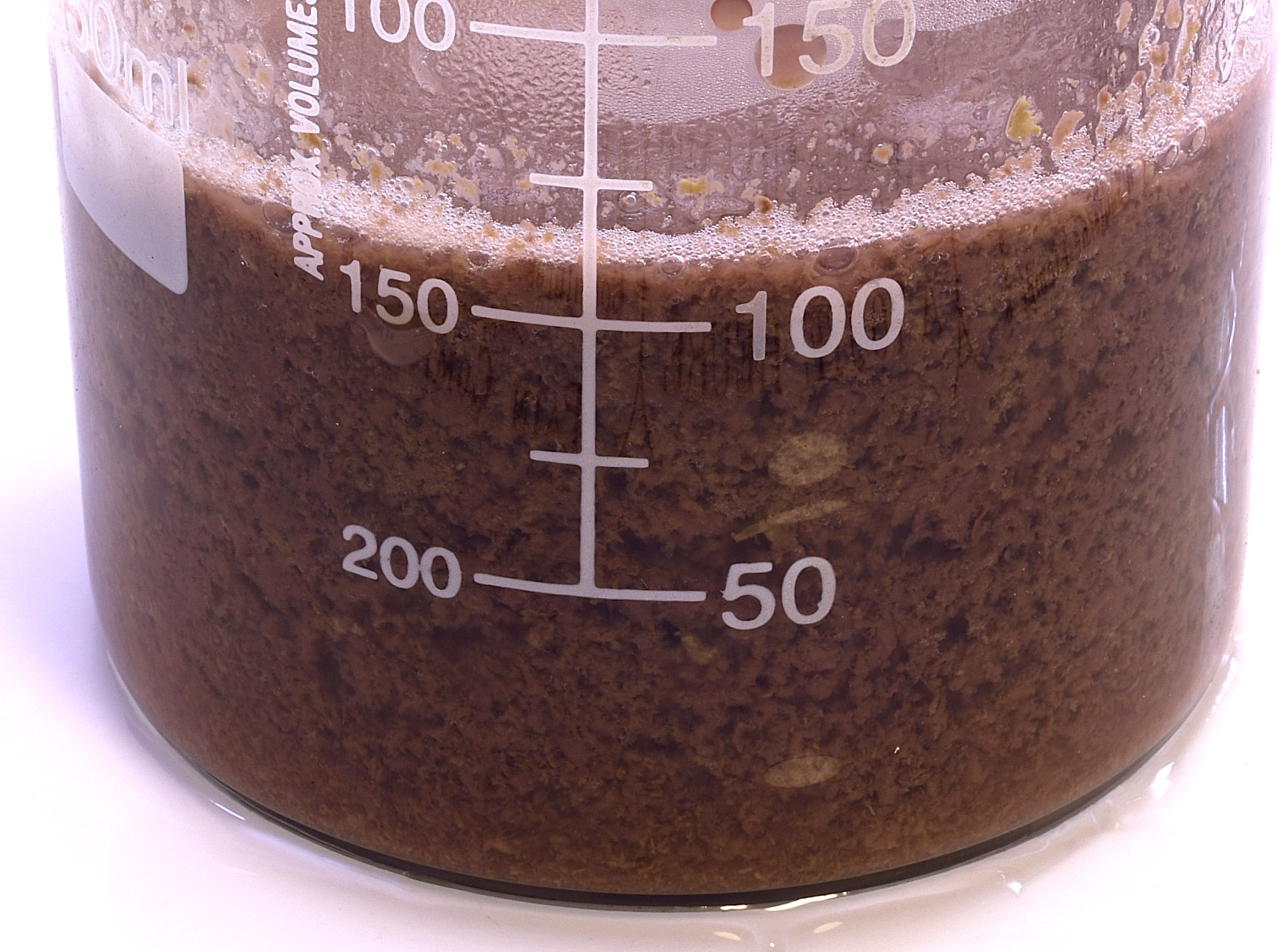

After being brought to 212 F/100 C, proteins solidify and stick to the albumins, forming either a raft or a sort of matrix.

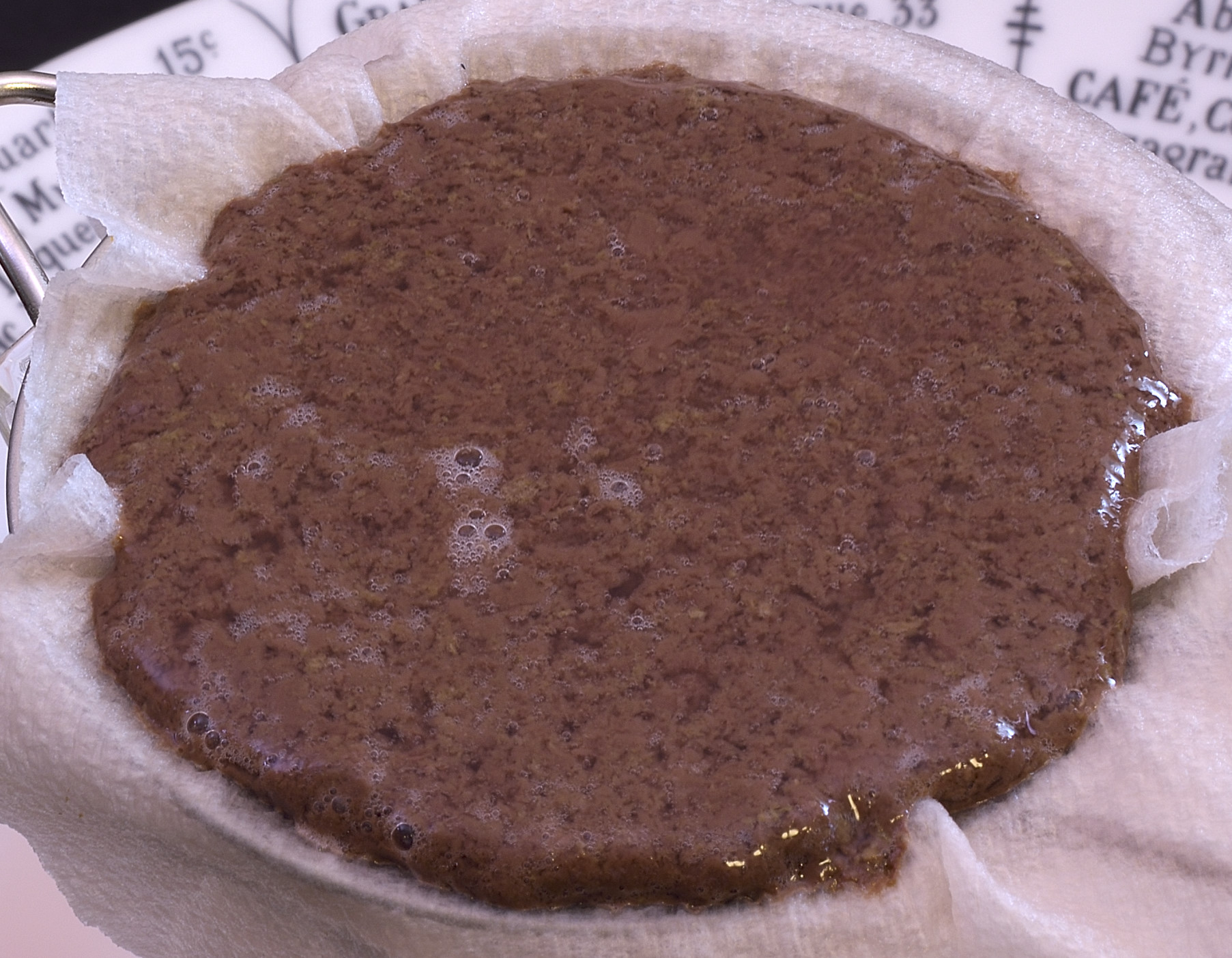

Paper towels are moistened so the juices pass through without clinging to the fabric.

You can fold over the corners and gently press down to encourage the flow–gently, Pilgrim.

Huh. 50 ml, that’s like 2 oz.

au naturel, patted dry.

Powdered egg white from a shaker/dredge. I use dredges for a lot of things–flour, powdered sugar. Make sure you mark them, you don’t want to get that stuff mixed up.

Mist with a cheapo spray bottle.

Flip it over, both sides.

A little more mist, but then you smear it a little, it will start to get sticky.

Kosher salt.

Both sides.

Cracked black pepper. Resist the urge to put garlic powder and other stuff in there. We’re going to make an emulsified “pan sauce.” That means we are going to utilize the debris/drippings from the steak that stick to the pan. If there’s garlic and other stuff in there, it could burn and introduce off flavors. We are going simple simple simple.

That’s right, pepper the other side too. Oil the steak lightly. I use spray release, or you can rub a few drops on it. Measure out 2 oz of cold butter–that’s half a stick. Trust me. This will make enough sauce for two people. Heat a saute pan to 350 F/176 C. Spray the pan with oil or add a few drops, but rub it out with a dry paper towel. Add the steak and sear all sides to the desired color. It’s better to add a few drops of oil during the process than to risk burning the oil in the hot pan before the steak even arrives. When the steak is fully seared, remove to a plate.

Discard the excess oil in the pan, reduce heat, and add the 2 oz sous jus that we harvested. It will start to boil immediately. Relax. Add the cold butter and push it around in the simmering juices with a fork as it dissolves. Increase the heat slightly. This really is the tricky part, but it’s just a matter of practice. The juices are slowly evaporating as the butter is melting. If there is too much evaporation the sauce will break, giving you melted butter. That’s not a crime. If not enough of the juices evaporate, the sauce is watery and has butter floating on top. Also not a crime. When you stumble backwards upon success…

it looks like this. It’s dark yellow because it’s about 80% butter, as per emulsion principle. After they get used to the thing of it, cooks put a little Worcestershire or acid or this or that in there to color and flavor, not part of the chemistry. I drew a little circle in it with glace de viande.

Other things we did from cold…

Other things we used…

Note: Right. Bison. Plains Indians. Corn, right?

Corn, to make creamed corn.

Corn, to make corn fritters.

White corn grits.

Popcorn.

White Navy Beans.

Blueberries, Oregon.

WAIT! HOW DID THAT GET IN THERE? Never mind….

Sweet potatoes, cooked sous vide @183 F/84 C X 45 minutes or thereabout.

Carrots, cooked sous vide @183 F/84 C X 45 minutes or thereabout.

Broccoli. I don’t want to sound like a broken record. What’s a record, anyway? Does anybody remember records? I do not cook green vegetables sous vide–they turn black. I talk about this elsewhere.

Bearnaise sauce, we’ll demo that one of these days.

Norm