Back when people still had tails

In my 20’s there was a fairly popular dish called Chicken Cacciatore. Ubiquitous in ersatz Eye-talian restaurants, it cluttered up a lot of “continental” menus as well. Back then we served a lot of quasi-French/International/American items like Stroganoff, Veal Oscar, Sole Meunière and Surf ‘n’ Turf.

Versions of Cacciatore even showed up in cafeterias and buffets, of which there was an abundance in those days. Sometimes they called it Chasseur, which is the French word for Cacciatore, which is the Italian word for “Hunter” or idiomatically “Hunter style.” Chasseur usually omitted the tomatoes and olives and was brown instead of red. Of course, most Americans had no idea what either Cacciatore OR Chasseur actually meant. With no internet to google, most diners hesitated to inquire in fear of being shamed for not knowing. Waiters and maître d’s had a reputation for mocking people that only spoke English.

The romanticized premise was that the ingredients might be gathered by a lone hunter on sojourn in the forest. Our devoted outdoorsman might either happen upon these items while rummaging through the thickets and underbrush, or have them stowed away in his haversack. He would forage in hopes of possibly snaring a rabbit, which could also be prepared “alla Cacciatore.” Was there a time when one might encounter a wild chicken in the woods? That would DEFINITELY be before my time.

Somebody surmised that this whimsically conceived hodgepodge of ingredients would include mushrooms, onions, peppers, fresh herbs, tomatoes and sometimes olives.

I don’t go back THAT far

Our culinary instructors’ eyes gleamed playfully as they explained the etymology of this dish. They would sigh wistfully as if they actually remembered such a time. Many of us knew even then that the designations of “classical” dishes depended on the suspension of disbelief for the sake of romance and imagery.

Veal Parmigiana is not the only way veal is served in Parma, and Fettuccine Alfredo and Caesar Salad did not even originate in Italy. Why should “Chicken, Hunter Style” be any different? Imagine if that was the way it was listed on stateside menus. People would say “that must have been some kind of hunter.”

The crux

Here’s the thing. Chicken Cacciatore can be very good, in a delightfully messy kind of way. If care is taken in the preparation it’s just as good as any other bone-in chicken dish. We used to do it with just the breasts too, but what would our deer-stalking friend do with the legs and thighs?

Old people are always quick to remind (everybody else) that there is nothing new under the sun and that everything comes back eventually. Wide lapels and leisure suits notwithstanding, we may actually see Cacciatore start showing up again on swanky menus one of these days–$45 instead of $5.95. There really was a time when $5.95 was pretty hard to come by.

Myself, I am grateful for civilization. Gas/electric stoves and other modern conveniences make this and many other dishes easier to prepare. Trying to cook over a campfire does not appeal to me whatsoever. I prefer a lot of ice in my beverages. Meanwhile, we can cling to fanciful monikers for the sake of a little melodramatic charm on restaurant menus. Something to talk about at the table.

Ingredients:

Chicken, 1 each, approximately 4 lbs/1.8 Kg, cut into breast, wing, leg and thigh pieces.

Kosher salt, 1 Tablespoon.

Cayenne pepper, 1 teaspoon.

Flour, start with a shaker full–about 5 oz dry/150 g.

Vegetable oil, 2 Tablespoons.

Sweet bell peppers, any color, 1 each; you can’t be picky in the forest.

Green onions, or of course, ramps! 2 or 3 each.

Mushrooms, 4 oz/120 g, about 30 slices. Crimini or chanterelles would authenticate, but let’s be realistic.

White wine, 4 oz/100 ml. A dedicated hunter would more likely pack a hip flask of cognac or grappa, if only to avoid the extra weight.

Tomato paste, 4 Tablespoons; sure, he could pack a tin.

Water, 1.5 cups/300 ml; fresh from the mountain stream.

Bouillon concentrate, enough to flavor 2 cups–foil wrapped cubes are pocket stable. Campers don’t make stock.

Fresh herbs, oregano, basil, even tarragon–whatever presents itself during your trek.

Butter, 4 oz/120 g. Not much chance of coming upon a cow and a churn in the woods, but butter will keep at room temp for a couple of days.

Cured green olives, 6 each. This guy must have been Sicilian.

Chopped fresh parsley, 3 Tablespoons.

Modern Equipment requirements

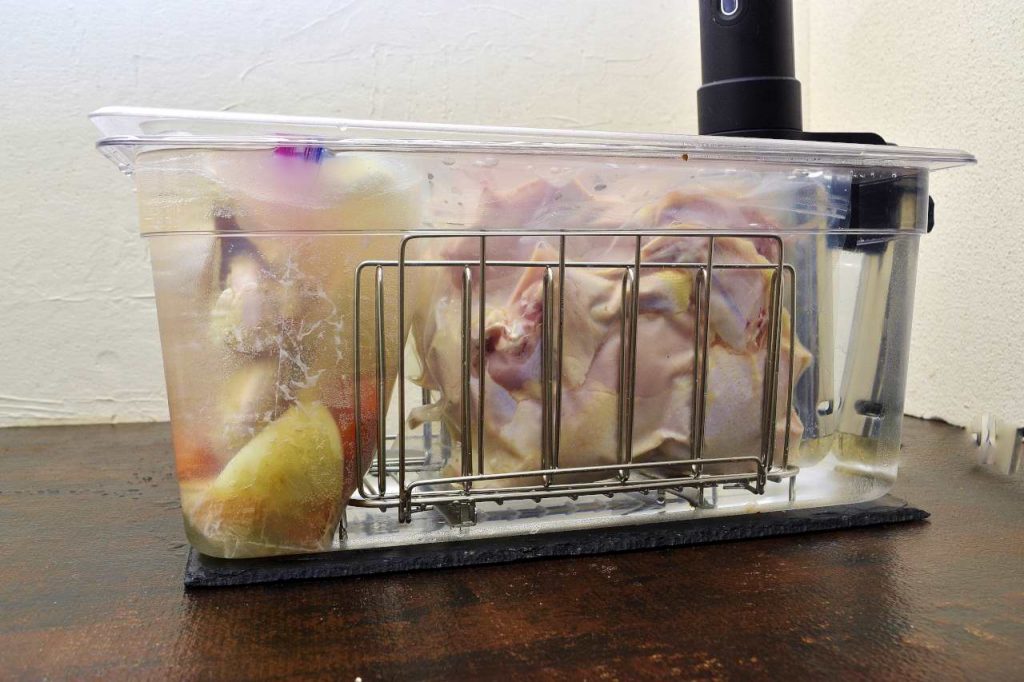

Immersion circulator, portable or stationary.

Heat rated container, minimum of 2 gallons/8 liters.

Heat rated sous vide bags, 2 each.

Flour shaker or fine meshed strainer.

Flat bottomed skillet, approximately 12″/30 cm. and 3″/90 mm deep.

Kitchen tongs, metal.

Infrared or probe thermometer.

Serves 2-3

Level of difficulty, 2.75

Procedure:

Dispatch and pluck your bird…seriously though:

Preheat the sous vide bath to

132 F/58 C.

Seal the chicken in single layers in 2 vacuum bags and stage into the bath. Process for a minimum of

5 hours. Up to 8 hours if that is more convenient.

This will pasteurize and preserve the chicken. After the time has elapsed remove the bags of chicken from the bath and submerge in iced/tap water until they achieve 70 F/21 C–about half an hour. Refrigerate to 40 F/4 C–this is necessary to assure food safety. As long as the bags are not opened, the chicken can be kept in this state for at least a week.

Quick, before the sun goes down

Scorch the bell pepper over the campfire. Oops. scratch that. Cut the ends off of the bell pepper and cut in half down the spine. Remove the seeds and pulp. Scorch the peppers with a propane torch or use the broiler function in your oven.

Leave a little black on the peppers. Cut into 1″/2.5 cm squares. Set aside. Starting at the green end, slice the green onions razor thin.

Stop slicing when you get to the white parts of the scallions. Trim off the root end and split lengthwise as shown.

Put the pouches of chicken in hot tap water (120F F/49 C) for 5 minutes. Cut open a corner of the pouch and pour out the melted gel. You can clarify it or save it for later. Cut open the pouch and stage the chicken on to a sheet pan lined with parchment or butcher paper. Leave a little moisture on the surface of the chicken–this helps the salt and pepper cling. Mix the measured salt with the cayenne. Sprinkle both sides with the mixture.

Now you want to dry the surface, so shake or sift flour lightly over both sides of the chicken. The flour doesn’t really have any purpose other than to prevent sticking. If you have enough flour on there to thicken the sauce, you have way too much.

You may attract a few curious onlookers–deer, raccoons, neighbors…

Heat the skillet until the surface achieves 225 F/107 C.

Add enough vegetable oil to liberally cover the bottom of the pan–about 1/2 cup/100 ml. Whether your bird is big or your pan is small, resign yourself to browning the chicken in batches. Why? If there is at least 1″/25 mm between the pieces they brown more evenly and faster too.

Shake the excess flour off of the chicken as you add 3-4 pieces to the pan, skin side down. Brown well. Do not over-flip. Be patient. Rotating the pan on the burner moves the hot spots/cold spots around. This also helps the chicken brown evenly.

Monitor the temperature of the bottom of the pan with an infrared thermometer, and toggle it up and down if necessary to keep the temperature somewhere between 200 F/94 C and 250 F/121 C. You will see just how wide a range of temperatures can occur in the bottom of a pan at the same time. This is why it is so important to LISTEN. Put down the thermometer and make sure the pan keeps sizzling.

It matters

In case you haven’t noticed, this is one of my pet peeves. Chicken dishes like this are almost always “rushed” in restaurants. Nobody thinks that doing it properly matters, but it has a huge impact on the end results. They just crank up the pan, crowd in the chicken and go back to whatever else they were doing–usually malingering.

Only turning the chicken once yields the best results. Use the tongs to lift it up and take a peek and check for color. It is unlikely to scorch at this temperature. Nobody ever thinks to listen to food cook. You should hear sizzling. If you hear hissing, your campfire is too cold. If you hear popping noises, your blaze is too hot.

Rotisseries are overrated

When the chicken takes on the desired color, turn it over and brown the other side. Again, don’t rush it–you can see above that I just scooched the first batch up and there was still room for the next batch. That’s a big pan. the You want the internal temperature of the chicken to be approximately 140 F/60 C.

Cooks always want to “simmer” (read “boil”) the chicken in the sauce to finish heating it because they are lazy, they were probably shown that way, and they mistakenly think it will cook faster and impart the flavor of the sauce into the chicken. It won’t. Only salt can penetrate the surface, and we already seasoned, right? Remove the chicken from the pan and set aside–keep warm, if possible. Most ovens have warming functions now, usually preset. You want somewhere around 170 F/77 C. Keep searing the pieces of chicken until they are all browned. When you are done, you may be surprised that there is more oil in the pan than when you started. Oil does not go in to the chicken. Oil comes OUT of the chicken.

You can pour out the excess oil, but these pans are heavy and spills happen. Put a couple of paper towels in the pan–see below. A little trick.

Racing with the setting sun

Increase the heat to high. There is still a little oil in the pan. Add the green onions and saute for one minute–avoid stirring, let them sizzle but pull them before they brown. Stage them into a small heat proof container, like another pan or even a plate. Add some mushrooms to the hot pan–make sure they all touch the bottom of the pan. Add a few drops of oil if necessary. If all the mushrooms don’t touch the bottom of the pan, you are not sauteing mushrooms. You are steaming mushrooms. When they darken and wilt,

remove them from the pan and spread them out flat.

Add the white wine to the pan to remove whatever drippings stuck to the bottom. Reduce the wine to almost nothing–wine provides flavor to sauces–NOT volume.

Add the tomato paste, the water, the bouillon powder, and whatever fresh herbs you were able to gather. If you clarified the gel from the pouches, add that too. Bring to a simmer and make sure it’s smooth. It doesn’t have to really boil or reduce. Not to worry, fresh herbs release their flavor immediately and then it’s gone for good. Taste for seasoning.

Return the mushrooms and green onions to the pan. Add the peppers and the olives.

Adjust to medium heat. Add the butter to emulsify. I know, that seems like a lot of butter. I have seen guys work three or four times that much in, so don’t feel too guilty. Keep stirring as the butter melts.

You will see that the texture improves as the emulsion forms. People scratch their heads when they fail to approximate their favorite dishes from their favorite restaurants, even though the chef provided the recipe. We almost always leave this part out, to protect our job security and because it is such a habit for us that we assume everybody else does it too.

Add the chicken to the pan skin side DOWN and then turn it over so it has a coating of sauce. Do not boil again. Everything is cooked, everything is hot, why would we boil it now? That ruins it. The butter starts leaking out and then you see it on the rim of your plate. Little puddles. Now you know something. Voila.

Assembly

You have come too far to just DUMP THIS OUT ONTO A PLATTER. Arrange the pieces of chicken on your serving surface and spoon the sauce over the top so the vegetables are visible. Sprinkle with the parsley.

The family style looks good, but sometimes people are hesitant to touch it for fear of making a mess or doing something stupid. I usually do the plating for guests.

Our avid sportsman could have some pasta in his rucksack, even though the idea of using a campfire to boil water for five minutes seems overly ardent. I had it, so I tossed it with a little foamed butter and used it for the solo presentation.